Learning Rust and Building a CLI

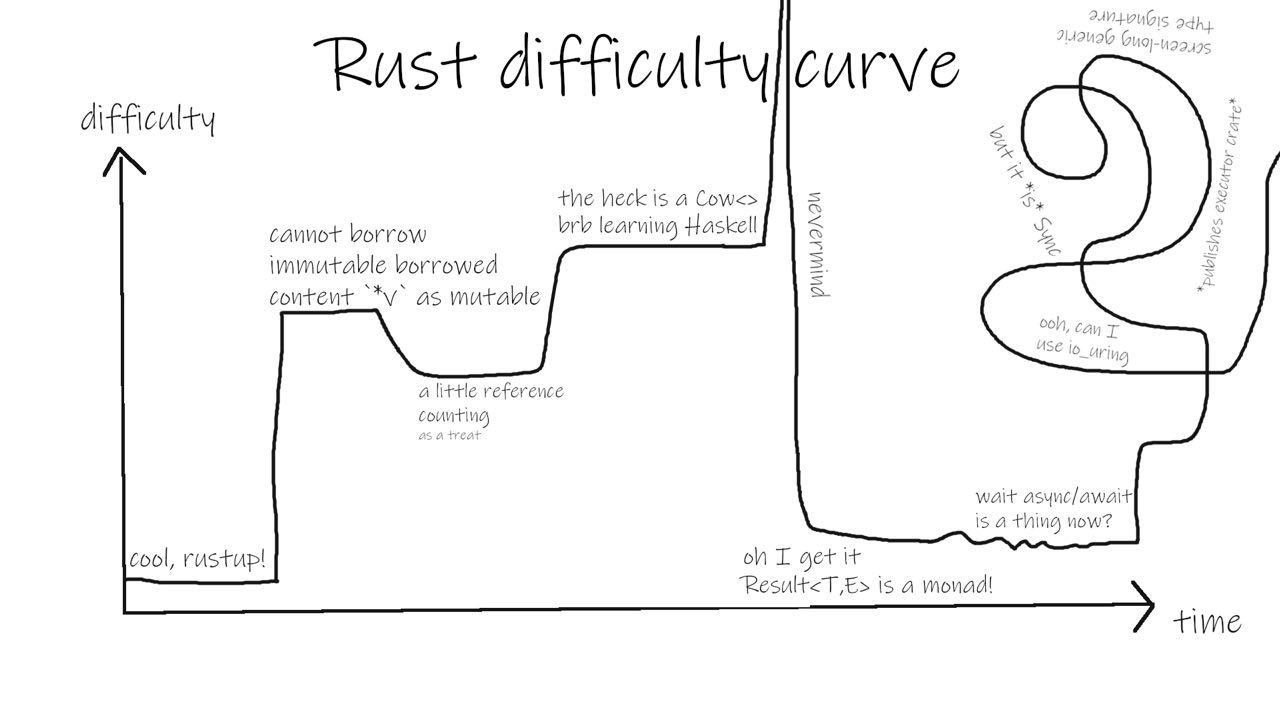

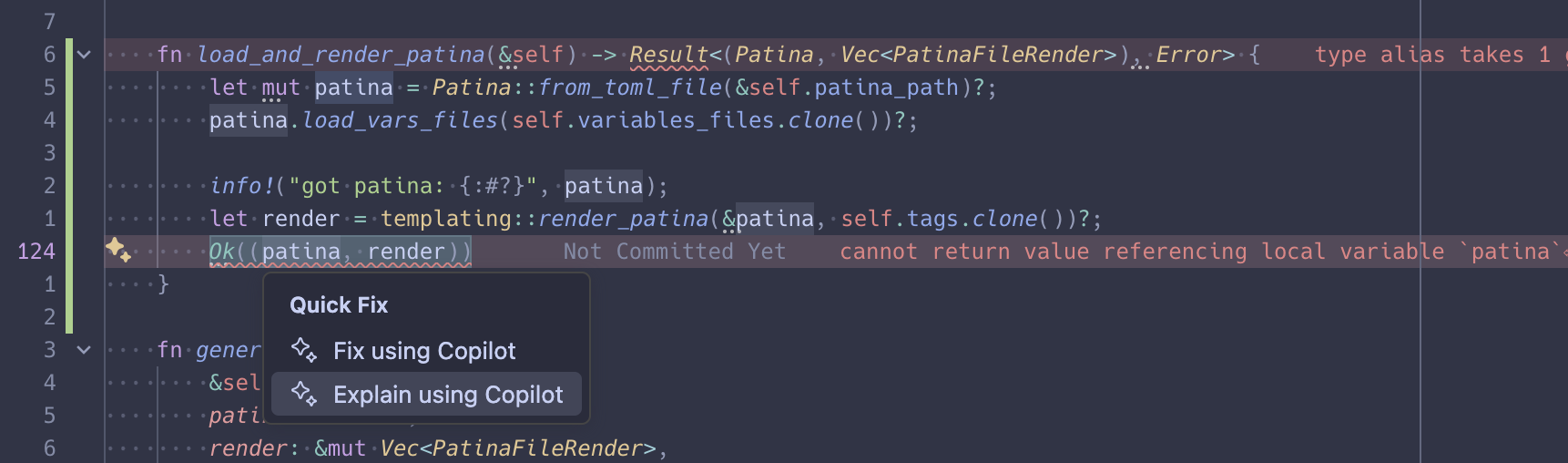

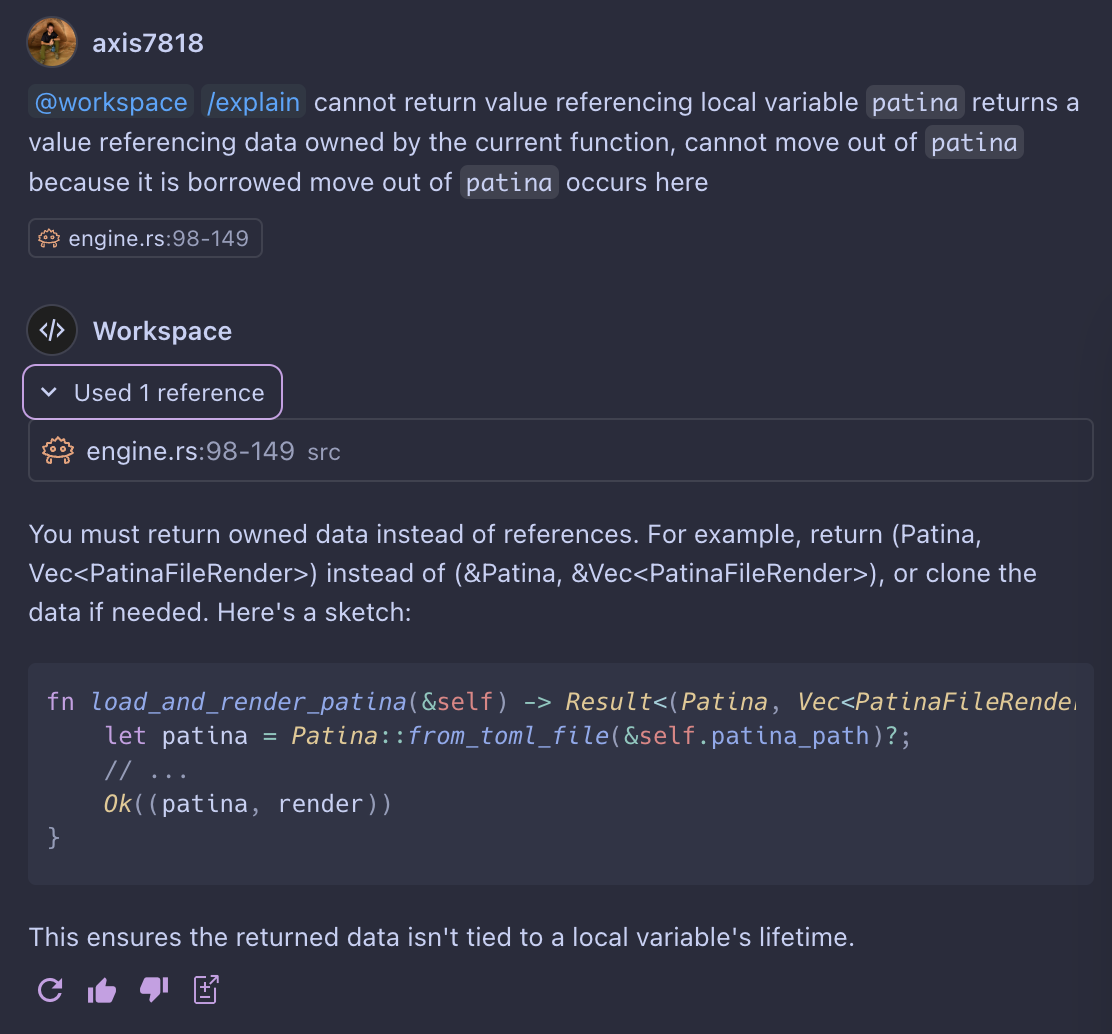

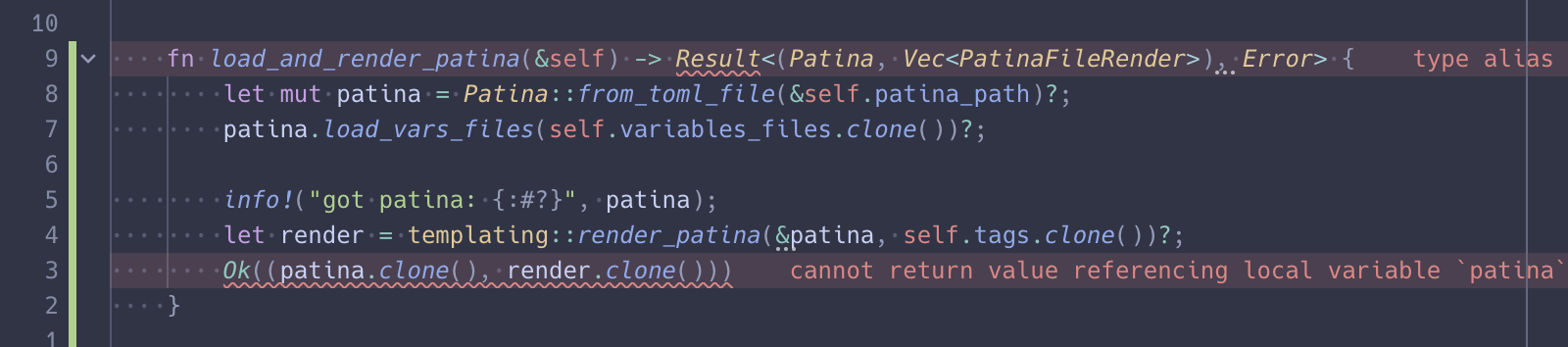

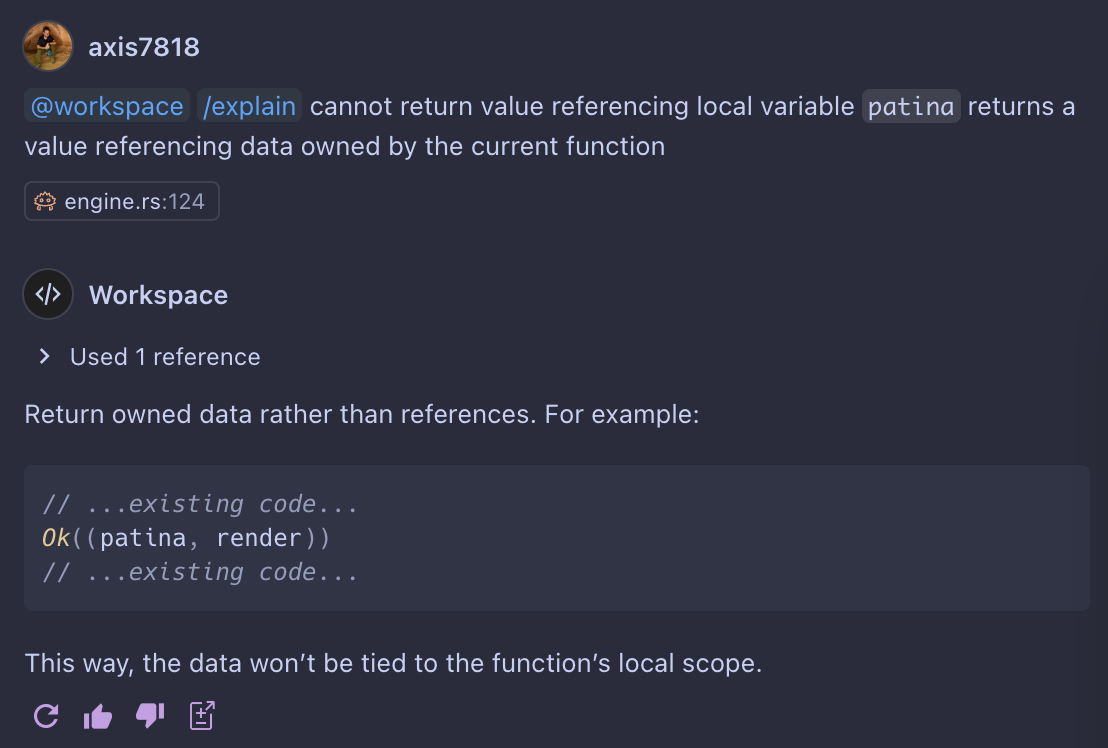

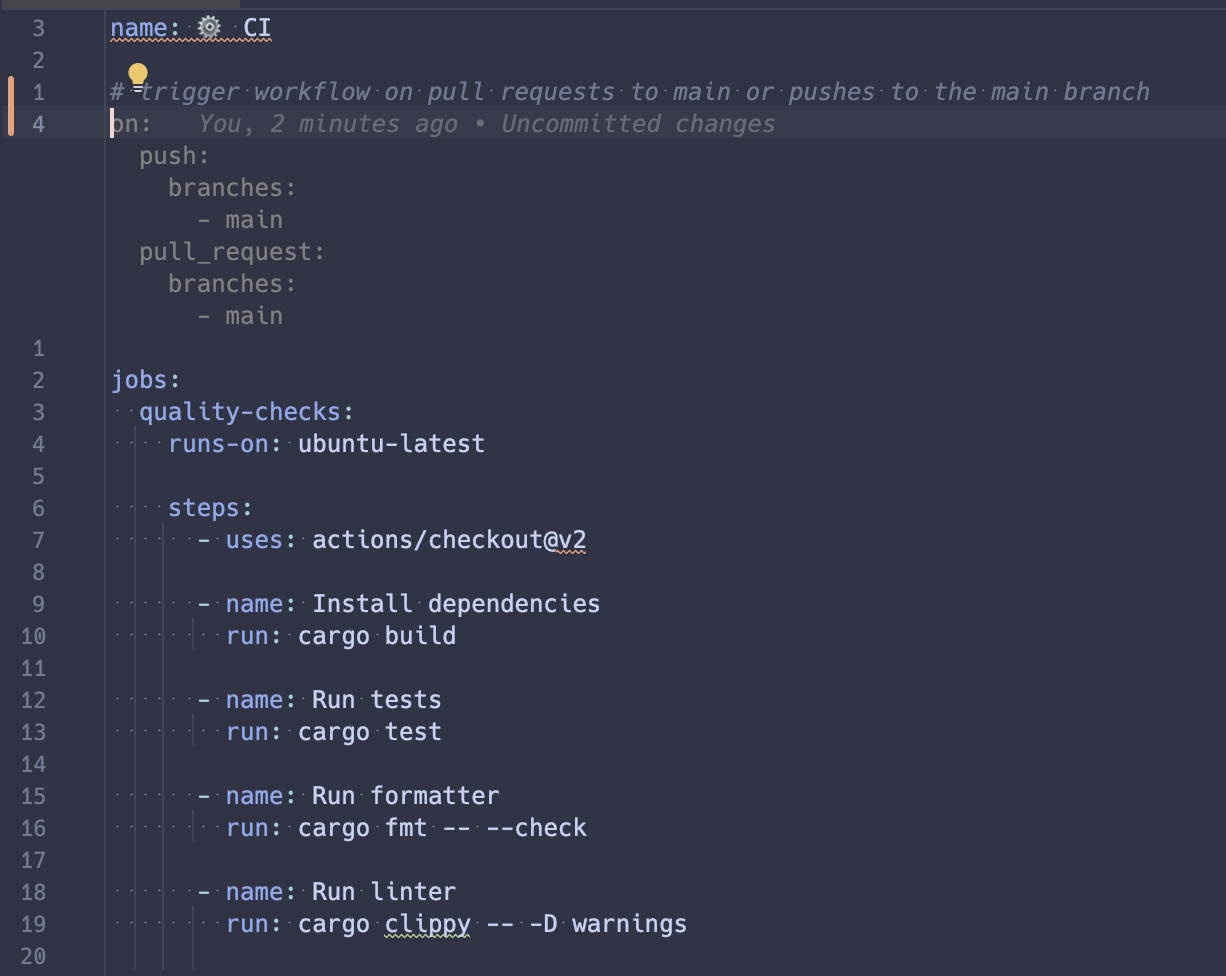

My experience learning Rust and building dotpatina Photo by Thomas Tastet on Unsplash Lately, I have been feeling a particularly strong itch to learn a new technology and just build something. This feeling is nothing new to me, as making stuff is my primary motivator and I am drawn to new technologies like a moth to a flame. So, I did what I do best and decided to build an over-engineered tool to solve a minor problem: managing configuration and dotfiles on my development machines. Over the course of a day, I use 3 different computers. My work MacBook, my personal MacBook, and my Windows gaming PC. On each of these computers, I install and configure the same set of software (ex: git, zsh, tmux). In order to synchronize configuration across machines, I set up a dotfiles repository. With my dotfiles repository cloned onto each of my computers, the problem became copying files to their expected filesystem location for the respective tools to use. This can be managed via scripts, but these scripts get tricky when files need to be slightly different for each machine. For example, on my work laptop, I want my gitconfig email address to be my work address rather than my personal one. I used this problem as an excuse to learn Rust and build a CLI utility, dotpatina. Dotpatina allows me to declaratively manage dotfiles using handlebars templating and renders diff visualizations to make it clear what files need to change when I update my dotfiles repository. Here is an example of it in action: For more information about dotpatina, see the GitHub repository. I chose Rust primarily because I have never used it before. And, its performance & memory safety guarantees sound like it would make a fun language for future projects. My objective was to build a “production ready” (in quotes because I have no expectations that anyone other than me will use dotpatina) tool from the ground up using a new language and toolchain. I just wanted to be a beginner again, and Rust’s famously steep learning curve seemed like the perfect choice. Before really building anything, I started with the general Rust tutorials. These were good introductions and served to introduce me to cargo, Rust’s toolchain, and concepts (like borrowing and lifetimes). Compared to learning other programming languages, Rust has great resources for gaining hands-on practice right from the start. And, many of these resources guide you through error scenarios and how to fix them. Too often, introductory material will stop after the happy path where everything works as intended. With Dotpatina, I didn’t just want to write the Rust code for a CLI. I wanted to write tests, publish it to a public place, and include documentation. I used Rust and cargo for running tests and formatting. This was one of my favorite parts of the Rust language because of how consistent the tooling is across cargo crates. The dotpatina create is published to crates.io automatically when changes are pushed to main. docs.rs hosts documentation for any crates published to crates.io. But, I also included documentation hosting with GitHub pages. While building dotpatina, I also tested two development environments: VSCode with the rust-analyzer extension and RustRover by Jetbrains. Generally, I found Rust Rover to be the better experience for working directly with Rust code. It is easier to run Rust tests, cargo commands, and viewing Rust library documentation. However, the GitHub Copilot experience (details below) was better in VSCode. After learning the basics of Rust, but before diving into Rust development, I decided to make a conscious effort to use GitHub Copilot (with the o1 preview model) as an AI programming assistant. This was my first honest effort using these tools on a “real” project. So, I will summarize what I thought about GitHub Copilot with tooling that I am not an expert in. My favorite use of GitHub Copilot is explaining errors. It doesn’t take long after starting a Rust program until running into your first compiler error. And, a regular part of working with Rust is dealing with the borrow checker. Since there are whole classes of compile time errors that would be runtime errors in traditional languages, it is very easy to provide error information as context to GitHub Copilot. Before too long, I found myself defaulting to GitHub Copilot to explain an error. Invoking the The GitHub Copilot chat view shows what portion of the code was referenced and explains a few potential solutions. In this case, returning values instead of references is the suggested solution. Except… the code is already doing that. And cloning doesn’t fix the error either. So, why is this my favorite part of using GitHub Copilot? Well, because it helped me explore the error as it related to my code specifically. GitHub Copilot generally accounts for specifics to my codebase that are provided via context. When simply searching for error help online, the search results are independent of the code subject to the error. It becomes the responsibility of the programmer to translate help to their codebase. GitHub Copilot helps with this translation. In other instances of explaining and fixing errors, GitHub Copilot would provide solutions that technically worked. These technically correct solutions fell into 3 buckets (in order of frequency): This experience did not completely replace RTFM or web search. The challenge seems to be identifying and providing the proper context to GitHub Copilot to generate a helpful response. But, it has become my first line of defense against the red underlines in my IDE. When it comes to actually generating code, I found GitHub Copilot to be particularly helpful in 2 places: very repetitive code and one-off tasks that might be done once per project. When developing software, I will almost religiously enforce DRY principals. The one constant exception to this is when writing unit tests. This allows unit tests to serve as self-contained examples as well. And, debugging tests is easier without the extra layers of abstraction that reduce repeated code. In addition to the repetitive nature, unit tests often have an explicit naming pattern. For example, test names might follow the template: The repetitive nature of unit tests and clear test naming creates perfect conditions for GitHub Copilot to generate large portions of code. In terms of pure time savings, I found this to be the most helpful use of GitHub Copilot. On the other end of the spectrum are one-off tasks. These are the tasks that happen infrequently enough that it is hard to become an “expert” in the syntax. When building Dotpatina, I created GitHub Actions workflows for continuous integration and continuous deployment. This is a one-time set up task and requires specific yaml syntax. A quick comment, and GitHub Copilot suggests the proper yaml for triggering a workflow under the desired conditions. Generative AI and AI Pair Programming is here to stay, and I believe Software Engineers will need to make use of this technology (where it provides real benefit) in order to stay relevant in the job market.However, I do have some concerns with generative AI’s impact on the industry. I worry about its ability to generate hidden technical debt, especially when code is not thoroughly reviewed by an expert. Even if code functions perfectly. Inefficient code is harder to maintain and makes less code less green. I worry about the accessibility of programming. Learning to code had been very accessible to people, only requiring a computer and an internet connection. While there are cheaper AI pair programmers and GitHub Copilot has a free tier, it is still expensive to get “quality and quantity” use out of AI pair programmers. And, I worry that the craftsmanship of computer programming will lose value. Although admittedly, this one makes me sound like a horse in the age of the automobile. Taking the time to learn a new programming language and complete a full end-to-end project was a fun exercise. Putting an intentional effort into using an AI pair programmer in this context let me evaluate GitHub Copilot as a tool without the pressures of deadlines or scrutiny of others. And, this has given me motivation for starting or completing other side-projects to satisfy my desire to build Software outside the context of my day job. Building on my new knowledge of Rust, I plan on exploring game development with Bevy or cross-platform app development with Tauri. I am also interested in evaluating Continue with local Ollama models as a more accessible AI pair programmer alternative.

Being a Beginner Again

Beginner Rust Resources

The Rust Software Development Lifecycle

VSCode vs Rust Rover

Learning Rust with AI Assistance

Explaining Errors

/explain quick action is just a keyboard shortcut away, and is much quicker than copying relevant error information, searching the web, and finding a relevant (probably Stack Overflow) link.

Repetitive or One-Off Tasks

Repetitive Code

One-Off Tasks

My Concerns with AI Pair Programming

Takeaways